Operation Snow Leopard

All hell broke loose within PLA

Following incursions by Chinese forces into Indian territory, tensions escalated significantly, reaching a peak during the crisis in the Galwan Valley on 15-16th June of 2020, when both Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed and many tragically lost their lives. Despite several attempts by the Indian side to diffuse these tensions through diplomatic negotiations, the Chinese response remained unyielding. In this atmosphere of heightened alert, both nations bolstered their military presence along the border. On August 29-30 and 30-31, 2020, against the backdrop of growing hostilities in the northern sector of Ladakh, Indian Forces conducted a strategic operation. Anticipating the movements of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), they successfully secured the ridgeline along the Kailash range, thereby positioning India to negotiate from a place of strength. This newsletter aims to shed light on the Spanggur Gap area of Chushul, the theater of this significant operation, and to underscore its strategic and tactical importance for India. Through detailed analysis, supported by maps and satellite imagery, I will highlight the critical role of this operation and offer insights into the mission and the exceptional personnel who executed it. The India-China border situation is complex, and I intend to produce a series of newsletters that will comprehensively explore different regions within the various sectors of the Line of Actual Control

Disclaimer: All information in this newsletter is available from open source. Maps and sketched markings are not to scale. Representation of locations are approximates & list is not exhaustive. Boundary representation is not authoritative.

Understanding Geographical Features of the Chushul Sector

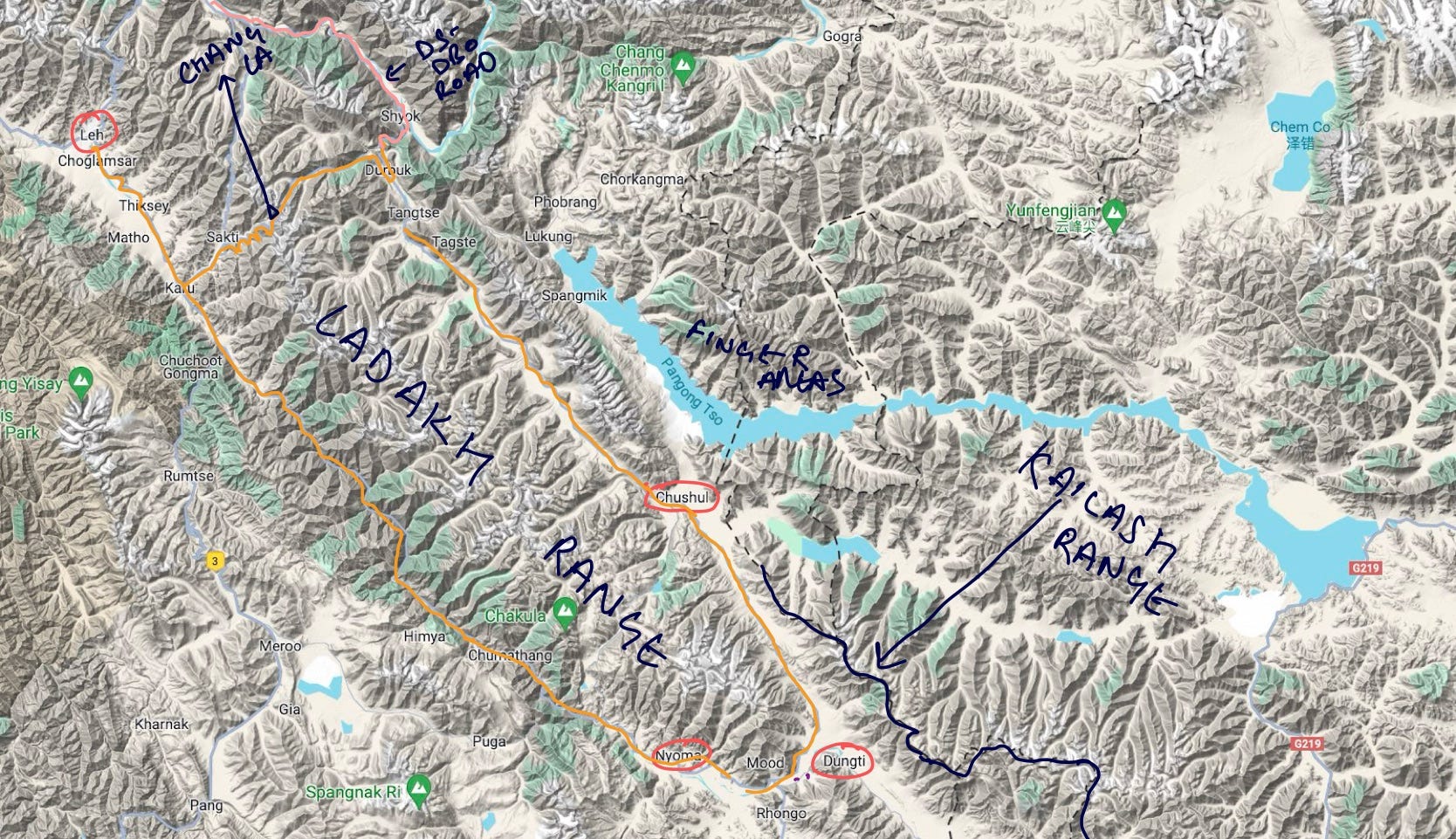

Image One, a terrain map of Eastern Ladakh, highlights key locations in this strategically significant region. In the left corner of the image is Leh, the most important area in the city, housing a major airport that serves both civilian and military purposes. Moving eastward from Leh is Darbuk, from where an all-weather strategic road extends to Daulat Beg Oldie (though this is not the focus of this newsletter).

To the east of Darbuk lie Lukung and Phobrang, situated close to one another. From this area, roads branch out towards Gogra, Ane La Pass, and the Fingers area on the northern bank of Pangong Tso. In the lower section of the map, Nyoma and Dungti are visible. The only road connecting Leh to the southeastern and southern parts of Ladakh is the Leh-Nyoma-Chushul road, which follows the Indus gorge, as depicted in Images 1 and 2.

This road bifurcates at Nyoma, leading towards Chummur. Further along, near Nyoma, the road splits again towards Undunkle. At Loma, another bifurcation occurs, with the northern route heading to Chushul and the southern route passing through Dungti. Here, the Indus River, originating in Tibet, sharply turns west and then curves north toward Leh, passing by Demchok.

Approaching Chushul, the road runs in close proximity to the Spanggur Gap and the Chinese claim line, which traverses the Kailash Range. Extending up to Dungti, the 370-kilometer-long Ladakh Range begins near the confluence of the Indus and Shyok rivers in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (POK). This range, with an elevation of 18,000 feet, presents a significant physical barrier from a military perspective, as it restricts lateral movement from east to west or vice versa. Any such movement must occur through the few high passes in the Ladakh Range, such as the Chang La Pass at 17,500 feet, which provides access to Darbuk, Tangtse, or Lukung.

The Leh-Changla-Tangtse road runs between the Ladakh and Pangong Tso ranges after exiting the pass and moves towards Chushul. To travel from Leh to Chushul, one must either navigate the steep gradients of the pass or follow the Indus gorge along the Leh-Nyoma-Chushul road.

Another notable feature in the region is the Pangong Range, which runs alongside Pangong Tso with an average elevation of 19,000 feet, offering no passes to facilitate lateral movement. Additionally, the Kailash Range, which served as a focal point during Operation Snow Leopard, includes notable features such as Rezang La and Rechin La, sites of historical battles. The Kailash Range starts near Pangong Tso and extends to Lake Mansarovar, with Mount Kailash located within this range.

Strategic Significance of Chushul & Spanguur Gap.

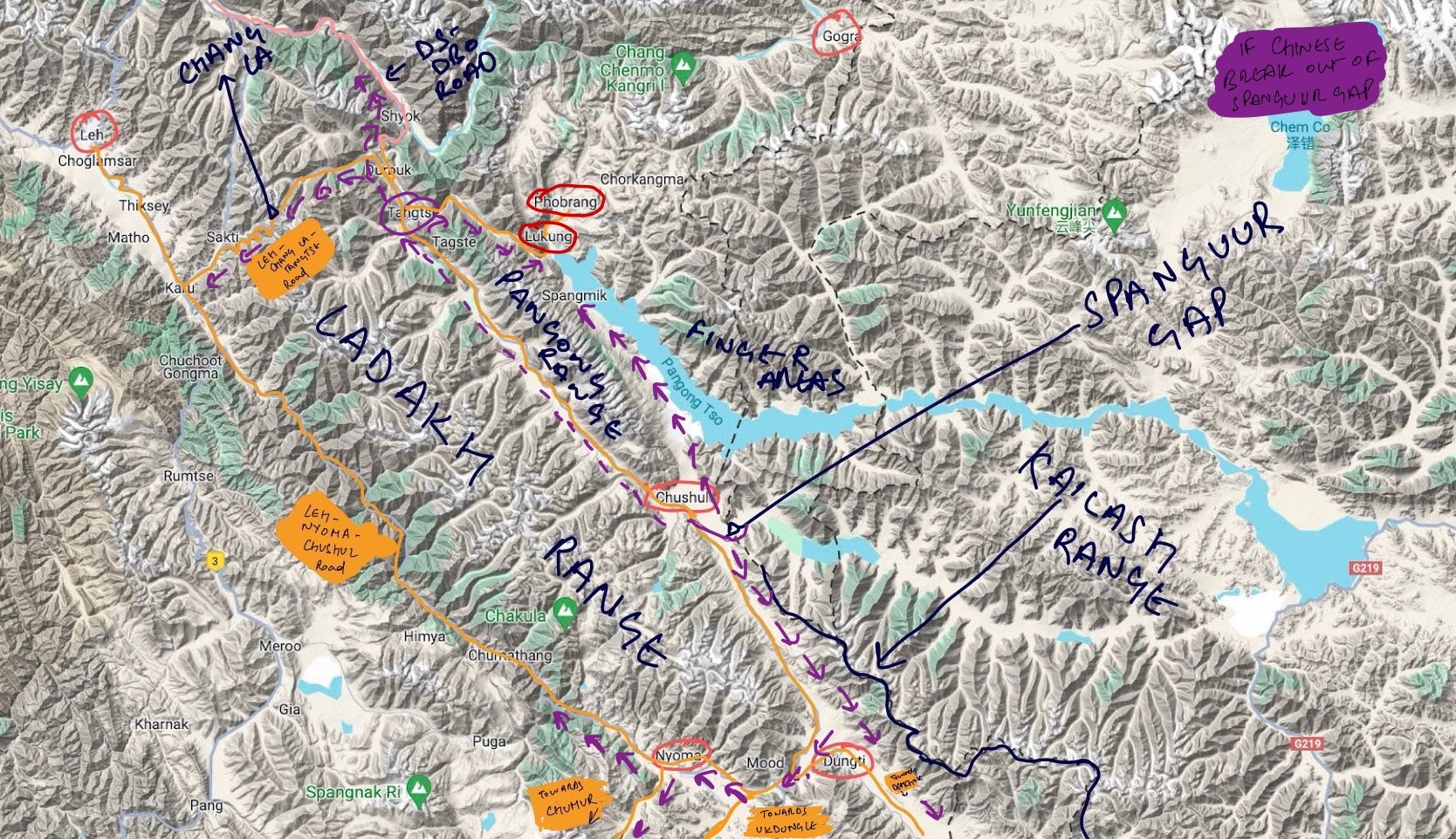

Chushul holds a strategically pivotal position in the region, such that any breakthrough by Chinese forces in this sector could pose a significant threat to Indian positions both to the north, including Tangtse, Lukung, Gogra, and the Finger Areas, as well as to the south, encompassing Nyoma, Dungti, Chumur, and Demchok. Chushul effectively serves as a linchpin; any setback for India in this area would have far-reaching implications for national security.

In image 2, one can clearly see the proximity of Chushul to the Spanggur Gap, where Indian forces are currently holding their ground against China’s People's Liberation Army (PLA).

Should the Spanggur Gap fall, the consequences could be dire. As illustrated in Image 2 with purple directional markers, the PLA could launch an offensive toward Tangtse along the Chushul-Tangtse road. From Tangtse, they could advance to occupy Durbuk, from where the DS-DBO road begins, potentially blocking this critical route or threatening Indian positions further north in the Daulat Beg Oldie (DBO) sector. Alternatively, they could move west from Tangtse to isolate Indian forces in the Gogra sub-sector and the Finger Areas, or move eastward to threaten the Chang La Pass.

Furthermore, if the Chinese forces were to advance south from the Spanggur Gap, they could threaten Indian positions in Dungti and potentially attack Demchok from the rear. Should they continue west of Dungti, they might extend their reach toward Chumur, Ukdungle, or Nyoma.

Can the Chinese Break Out of the Spanggur Gap?

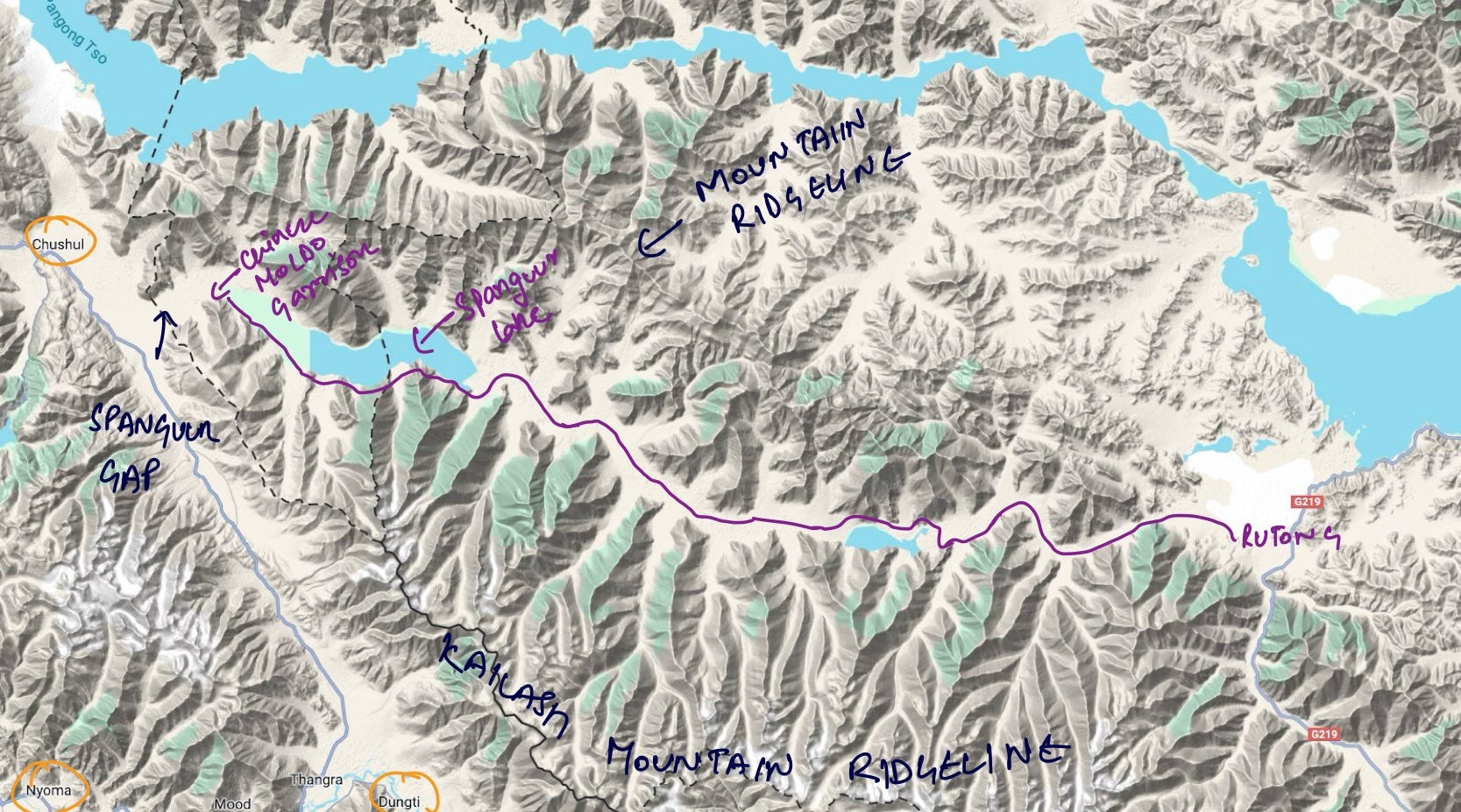

In summary, a breakout by the Chinese from the Spanggur Gap is neither simple nor straightforward. As illustrated in Image 3, a terrain map of the localized area, one can observe that the road from Rutong runs to PLA’s Moldo Garrison, passing through a narrow funnel between the Kailash Range on one side and another mountain ridgeline on the other.

Given this terrain, the only viable option for the People's Liberation Army (PLA) would be to advance along this road in a single file, with no possibility of lateral movement, particularly along the section that runs alongside the shore of Spanggur Lake. This funnel is at most 4 kilometers wide and contains multiple chokepoints throughout. An off shoot of the road on the rear of the Spanguur lake breaks away to go towards Chuti Chang La from the other side of the lake, as depicted in Image 7 below.

Regardless of the heavy armament, the PLA might deploy, they would find themselves constrained by this funnel. Moreover, as the funnel remains perpetually vulnerable if India takes control of the heights of the Kailash Range, as we will see later, any substantial movement by Chinese forces would likely be detected by Indian surveillance. Should the need arise, Indian forces will be well-positioned to inflict significant damage on the PLA, either through artillery strikes by the Indian Army or air-to-ground attacks by the Indian Air Force.

Key Features Around Spanguur Gap

( Blue colored: Indian Positions; Yellow & Violet: Chinese Positions)

On the southern bank of Pangong Tso lies the Pangong Range, characterized by several key features:

Helmet Top: This position is located closer to the southern bank of Pangong Tso.

Black Top: This vantage point offers a commanding view of both the south bank of the lake as well as the Spanggur Gap and the Chushul Bowl. It is of strategic importance due to its location, from which the Chinese have deployed surveillance devices to monitor movements in the area.

The Chinese access Helmet Top and Black Top from the rear, highlight their tactical significance in the region.

Key Features of Kailash Range:

Mukhpari: It is a strategically significant vantage point from which Indian forces can observe Dorje Unjum, a Chinese garrison, as well as other installations around Spanggur Lake. As the first key position in the Kailash Range, Mukhpari offers an unparalleled 360-degree view of the surrounding area. This location also provides a clear line of sight to the route connecting Black Top and the South Bank, which is maintained by Chinese forces and passes through Chuti Chang La, falling under direct observation from Mukhpari.

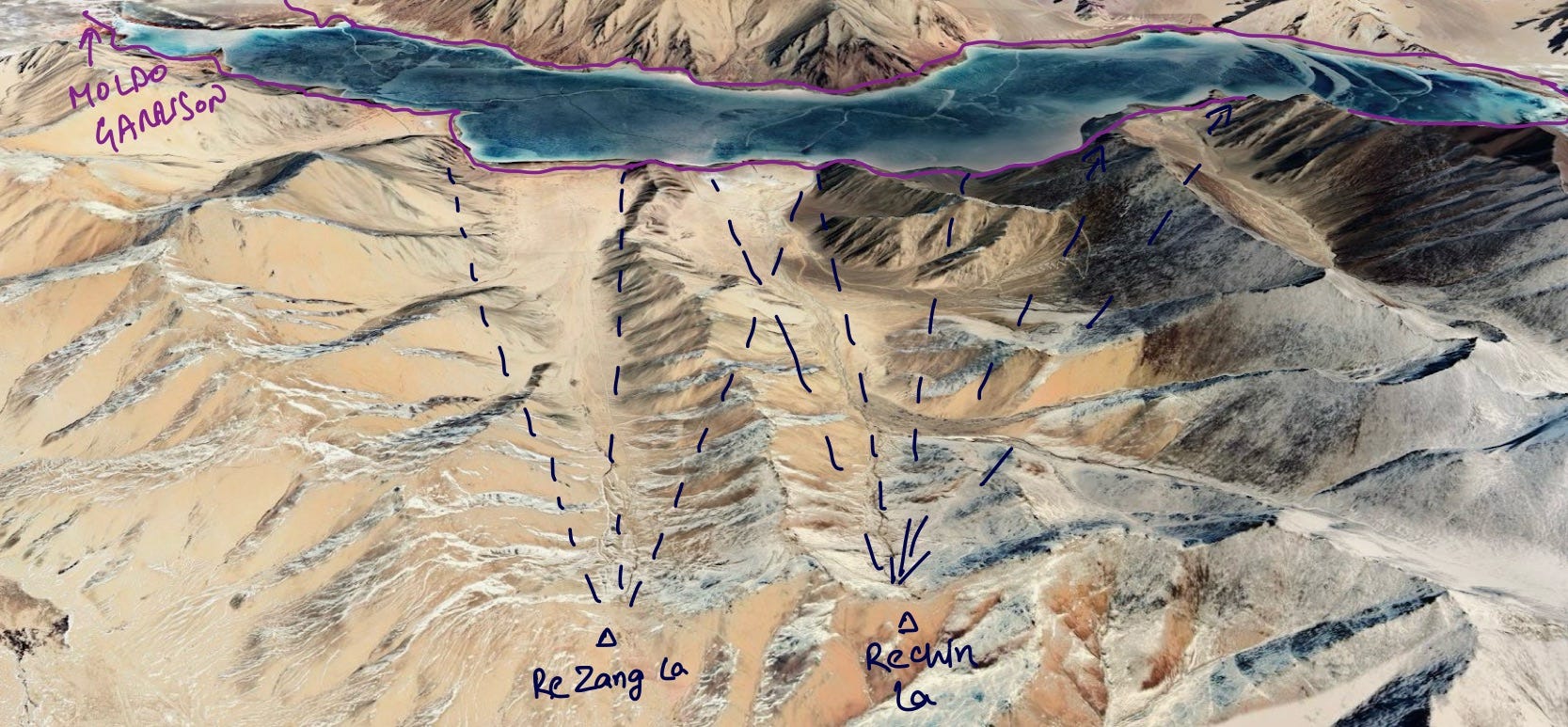

Rezang La & Rechin La: Another key features that had seen battles in 1962. These features, if occupied by the Indian Forces, allow them to dominate the movement of chinese troops along the spanguur lake.

Preparations for a Possible Snow Leopard

Following the Galwan crisis, which marked a breach of border agreements by China, there was a profound sense of mistrust in India regarding China's actions in the region. The reluctance of the Chinese to return to the status quo ante after a series of incursions further exacerbated these concerns. In response, the Indian Army Headquarters decided to develop contingency plans in preparation for any potential escalation.

In an interview with Nitin Gokhale, then-Lieutenant General Savneet Singh disclosed that he had been tasked, in his capacity as the commander of the 17th Strike Corps, to conduct an assessment of the situation in eastern Ladakh in July 2020. Based on his findings, Singh, in coordination with Army Headquarters, formulated various contingency plans.

What Happened on the 29-30th August 2020?

Only at the end of July and the beginning of August 2020 was Lieutenant General Savneet Singh ordered by Army Headquarters to move to Eastern Ladakh and prepare to launch contingency operations if necessary. On the night of August 29, 2020, local Indian military commanders detected Chinese movements aimed at dominating Helmet Top (Image 4) and Black Top (Image 5 & 6) to prevent Indian forces from occupying these strategic positions. Recognizing the implications of the Chinese actions, the highly decorated Northern Army Commander, Lieutenant General YK Joshi, directed the nearest brigade stationed at Chushul to ascend the heights. However, the Chinese forces reached the positions first.

To avoid a stalemate, Lieutenant General Joshi consulted with the commanders of the 14th and 17th Corps, Lieutenant General Harinder Singh and Lieutenant General Savneet Singh, respectively. They decided to implement one of the contingency plans previously developed by Lieutenant General Savneet Singh. By the first light of August 30, Lieutenant General Joshi anticipated that the Chinese might attempt to dominate other key heights in the area, which would place India at a severe disadvantage. Consequently, on that Sunday morning, he contacted Army Chief General Naravane to request authorization to execute the contingency operation. Although the Army Chief was attending a high-level meeting, Lieutenant General Joshi, leveraging his experience at Army Headquarters, managed to reach him and secure approval for the operation to occupy the ridgeline of the Kailash Range. By midday on August 30, a small formation of Indian troops began ascending the heights of Mukhpari (Image 7), Rezang La, and Rechin La (Image 8) to secure these critical positions, taking advantage of the cover provided by the Kailash Range. By nightfall, a substantial number of Indian troops had established positions along the ridgeline.

According to Lieutenant General Singh, later that night, the PLA likely detected Indian troop movements on the Kailash Range using their surveillance devices, and Indian forces observed some vehicular activity on the Rutong-Spanggur road. However, no significant actions were taken by the PLA, allowing India crucial time to build up and consolidate its forces on the Kailash Range. Throughout the night, Indian forces established supply lines, particularly for food and water, to ensure the troops were well-provisioned. India also had a quality track that allowed vehicles to reach Rechin La.

India had not occupied these heights since the 1962 war, and only patrols had ventured there previously. The movement of Indian forces took the Chinese by surprise, but what truly unsettled them was the presence of Indian armor on these heights. According to Lieutenant General Singh, it was the Chinese who first attempted to deploy armor, while India had kept its armor in close proximity as a contingency measure. Only after observing the Chinese mobilization did India decide to mirror their deployment and bring its armor out from concealment. This resulted in one of the largest build-ups ever witnessed along the Line of Actual Control between the two countries. From their positions on the Kailash Heights, Indian forces could observe the Chinese armor build-up below, which, in Lt. Gen. Savneet Singh's words, was a “suicidal” maneuver for the Chinese, as India, controlling the high ground, could easily target Chinese activities.

Nevertheless, Lieutenant General Joshi was not finished with the Chinese. On 31 August, troops from the 39th Division of the 14th Corps occupied higher points of Finger 4 on the northern bank of Pangong Tso, while Chinese forces had been entrenched on the slopes of Finger 4 since May. This maneuver placed the Chinese at a significant disadvantage, as they found themselves encircled by Indian soldiers occupying major heights in the region.

This operation to seize the commanding heights was named Operation Snow Leopard. It successfully put the Chinese PLA on the back foot, as every movement of the Chinese forces came under the observation and potential targeting of Indian armor.

Post Operation Snow Leopord

The operation of the Indian Army brought the Chinese to the negotiating table to disengage. However, it still took five months for the first set of disengagement. Soon, as the Chinese withdrew, India also withdrew from the Kailash Ranges. In an interview with Nitin Gokhale in 2021, Lt Gen YK Joshi, observed, “Absolutely. That action finally turned the tables on the PLA and got them back to the negotiating table. Before August 29-30, we had already conducted five rounds of discussions at the level of Corps Commanders. At that time, we found ourselves in a relatively defensive position. While we had established control over specific areas on the north bank, the Chinese held advantageous positions in certain key locations. However, a significant shift occurred following the events of August 29-30. With our occupation of the Rezang La and Rechin La complex, which are notable commanding positions overlooking China’s Moldo garrison across the border, the dynamics changed. We extended our presence to the south bank and secured higher elevations, including Finger-4, thus gaining dominance over the regions previously held by the PLA. This strategic move played a pivotal role in compelling China to re-engage in negotiations. The meticulous planning and execution of our operations took the PLA by complete surprise. Their lack of anticipation for such actions stands as a testament to the dedication of our ground troops and the adept leadership that masterminded and rehearsed these manoeuvres. Our preparation, ongoing since the Galwan incident on June 15, culminated in this decisive action that caught our adversary off guard, thus restoring the element of surprise on our side.”

Based on the strategic relevance of Chushul, as discussed above, it is critical to look at the Operation not just from a tactical view of bringing the Chinese to the negotiating table but also to keep them behind the Spanguur Gap.

Some additional open source images for more context:

This newsletter is dedicated to the brave men in uniform who, in November 1962, were ordered to defend Rezang La to the last man and the last bullet. They carried out their orders with unwavering courage and determination, fighting until the very end.

Additional Resources: